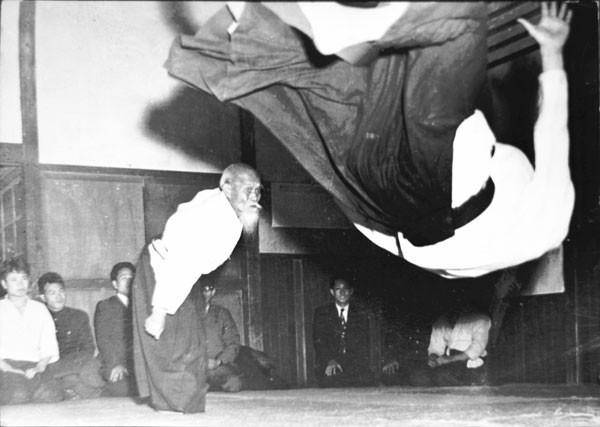

There are dozens of stories told by O’Sensei’s aikido students of being thrown by the master. They mostly follow a pattern: Upon attacking O’Sensei, they would be drawn into a black void, from which they would be hurled out onto the mat, gasping for breath.

One of the best descriptions was written by Mitsugi Saotome, who went on to become a famed sensei in his own right:

“Still now, I don’t understand receiving ukemi from O’Sensei. My consciousness returns to those experiences time and again, the flashback vivid and total. But sometimes I’m immersed in blinding light, complete light, and sometimes it is a complete, dark world…sometimes being thrown as far as 30 feet.” (Aikido and the Harmony of Nature, 1993).

It was an indelible experience, no doubt about that, but I always found such stories slightly suspect. The life and capabilities of the founder of Aikido have been mythologized to an uncertain degree; there are stories relayed by his biographers of him suddenly vanishing from in front of an opponent, and re-appearing behind him, of being able to see and dodge bullets during his service in the Sino-Japanese War, of being attacked by multiple men simultaneously and emerging from the pile-up victorious, with bodies flying about him.

The last is, to a degree, certifiable, as there are videos of him in his later years doing precisely that. Of course, this was when O’Sensei had already become a living legend, and those attacking him were his students, so to what degree they unconsciously collaborated with their teacher’s evidence of infallibility cannot be known.

The second, the ability to dodge bullets, was told by O’Sensei himself, as a description of the changes that occurred to him personally through his study of budo. The story would lack credibility objectively except for the fact that this was O’Sensei’s perception of his own experience. He was not divining for hero status — that had long ago been achieved — but likely attempting to translate an illogical, non-linear experience into language. If you ask any enlightened Buddhist about his satori, you’re likely to get similar malarkey. It’s not that it didn’t happen; it’s just that it’s an experience that doesn’t lend itself to easy description, so we rely on metaphor and image, sometimes ridiculous, to get the point across.

So these stories of being thrown by O’Sensei, all of a mold, make sense. It was certainly an experience like none other, being thrown by one of the great martial artists of modern times, an event worthy of remembering and relating. Like being knocked out by Mohammad Ali, it’s a hell of a good yarn, even if you were his sparring partner and it happened more regularly than you would wish.

Still, though, I always suspected these stories relating O’Sensei’s throws of a bit of hyperbole, just as you would might add a little extra force to the King of Boxing’s punch, the one that sent your body to the mat and your head to the showers.

And then it happened to me.

It wasn’t O’Sensei that threw me, it was my own sensei. But the event happened exactly like those other descriptions. It’s not hyperbole.

We were near the beginning of an otherwise nondescript class. Sensei had us working on throws from ushiro-nage, attacks from behind. We were on perhaps the second iteration of throws, and I was working with a partner up near the kamiza, when Sensei wandered over to offer a correction to my form. She had me do the attack so that I could understand what her form felt like when she did the throw. And that’s when it happened. I attacked her, and was suddenly sucked up into this black hole. I have no idea what happened after that, only that the next thing I knew, I was lying sunny side up on the mat, gasping for breath. Sensei nodded to me like absolutely nothing happened — her “you get what I’m saying now?” nod — I confusedly nodded back, and she wandered off to help another student.

That was it. It all took maybe a few seconds to happen. I staggered to my feet and leaned on my thighs trying to catch my breath, signaling to my training partner that it might be a few more seconds before I had my wits about me. Then we started up again, slowly, as I was still recovering my breath.

I never really did quite get there. I heaved and wheezed the whole class through. Granted, the class was almost entirely ushiro attacks, and was perhaps a bit more exuberant than usual as a result. But this wasn’t my first rodeo. I know how to pace myself. But it wasn’t until the last few minutes that I managed to fully recover.

In recent weeks, I’ve been really focusing on my center, my hara, the place in the body from which, in the Eastern martial arts, all ki, or ch’i, flows. Also known as the tanden, it is located behind, and a few inches below, your navel. In ki meditation, you inhale as you visualize ki coming in with your breath, directly to that spot. As you exhale, ki leaves the tanden and exits through your mouth with your breath.

More complicated circulation patterns are taught in disciplines such as tai chi or qi gong, but in practical application, you “extend your ki” through extremities, such as your hands, to bolster your movements without resorting to physical strength. Whether one regards this as merely a visualization exercise, or the actual manipulation of an animistic force, it is effective in creating a different kind of response.

So keeping my center, keeping my ki energy directed, has all been part of my aikido practice of late. I make sure I sit for several minutes before class doing breath meditation, and during our warm-ups, I’ve been focusing on strengthening and initiating movement from my tanden.

When Sensei threw me, that clearly-focused center was blown apart, and it felt like my ki was scattered across the mat. That was why it was so hard for me to catch my breath the rest of the class, and it wasn’t until Sensei had us cooling down with some simple, basic pins that I was able to gather myself together.

At one point, one of my training partners looked at me with concern. “Are you ok, Avery?” he asked.

I waved him off. “I’m fine,” I said. I love how, in an environment where we, frankly, spend most of out time trying to bash each other’s heads or origami each other into painful pins, we simultaneously show concern for each others’ wellbeing. I think a lot of the guys go easy on me too, since I’m one of the old guys of the bunch. Sometimes I think they feel like I’m a little fragile. They might be right, too.

Whenever Sensei has thrown me in the past, I have been able to tell that she is throttling back. Which only makes sense; she is ensuring her student’s safety, and usually trying to emphasize some aspect of the technique that she wants us to understand. But in that singular throw, it didn’t feel like she was holding back at all. There was enormous power moving my body with tremendous force.

On the other hand, it didn’t feel like she was throwing me particularly hard, either. I’ve been thrown hard by a variety of sensei and students, and I’ve also given some pretty hard throws to others. I know both sides of that coin, and this wasn’t that. It was like she was just — just throwing me. In the same way that she would just cross the street. Like there wasn’t anything unusual or different in what she did, it didn’t have a special spin or torque or windup on it, it was just another throw.

That feeling was confirmed for me after class. As the junior students were cleaning the mat, I wandered up to her.

“You really O’Sensei-ed me in class,” I said

She looked at me, confused.

“That throw,” I said. “It was like getting thrown through a void, the way O’Sensei’s students used to describe it, and then you’re lying on your back, gasping for air and wondering what the hell happened.”

“When did I do that?” she asked.

“Second or third technique you showed us,” I said.

Sensei frowned for a second, trying to remember anything unusual. “Really?” she said. She smiled and shrugged her shoulders. “Thanks for telling me.”

To her, it was clearly nothing special. It was just another throw. But its execution must have been flawless, I reasoned. Or there was something else going on.

I puzzled over it for much of that evening, going over that throw again and again in my mind. I didn’t draw much from my musings in terms of how it was done. I did, however, realize something else. To a large extent, since I’ve returned to the dojo and the study of this martial art, I’ve had no long-term goal. Nothing to settle my sights on. That can be good, in the study of the Eastern martial arts, where greater determination to make progress can often lead to slower actual advancement. On the other hand, the lack of ambition can lead one into a self-satisfied laziness.

But, looking back, my immediate emotional response to the throw — after “what the hell just happened?” — was “I wanna do that.”

Indeed, that’s the aikido that I want to be able to do, that I need to be able to do. Soft but immensely strong, controlled but swift, controlling without damaging. That’s what I’ve been on the mat all these years trying to learn.

And I just now figured that out.