It was a bit unexpected, the conversation that Sensei and I had. It was a few months ago; she pulled me aside as I was getting ready to leave the dojo after class.

“Avery, I wanted to let you know that I’m recommending you for nidan at the seminar in December,” she said. Nidan is the the name for the second-degree black belt level. For the past decade, I have been a lowly shodan, a first-degree black belt. To be honest, I had been quite happy there.

Oh, shit, I thought. I’m going to have to do some serious training in the next two months. All of a sudden, there was a test in front of my face. I hadn’t taken an aikido test in 10 years, and the last one I took was also at the December seminar in New York. To this day, it ranks as one of the most stressful days of my life, matched only by taking my board exams to become a doctor, and exceeded only by the birth of my daughters.

Sensei saw the deer-in-the-headlights look on my face, and understood my fear. “No, no,” she said. “You won’t be taking a test. I’m putting you in for promotion on my recommendation.”

My face brightened at that news. I was relieved at the “no testing” bit, but I was still trying to process the whole thing, mentally and emotionally. “Thanks, Sensei,” I said. “That means a lot.”

It did. And it does. But what it all means is something I’m still trying to put together. I had a lot of questions, for Sensei and myself, beginning with “why”, but I’m not sure that I could ask her that. There are some things you just don’t quiz a sensei about, and their motivation for things tends to be one of them. The questions I have for myself — well, that’s just a bag of snakes I’m not so willing to open.

I have always had an uneasy relationship with my rank in the martial arts, boiled of two parts self esteem issues, one part my natural orneriness, and one part my concern with how rank is viewed by others.

Ranking in aikido, as in most of the Japanese martial arts, is a modern creation. In the traditional schools, which preceded modern arts like judo, aikido and karate, one was simply a student until granted a menkyo, or license to teach the art yourself. You were either a student or a teacher, or in the case of being granted a menkyo kaiden were a master teacher and possible successor to the founder.

Ranking was created by Judo’s founder, Jigoro Kano, as a way of keeping students enrolled and involved with intermediate rewards. As you rise in rank, your belt changed color, from white to orange to yellow to green…ending with the transition from brown to black.

It is true that, to a great degree, rank means nothing. On the other hand, in the hands of an ethical teacher, rank is at least a reflection of one’s dedication to the art over an extended period of time.

Aikido is a little paradoxical about its ranking system. All of the levels (one starts at 6th and goes to 1st kyu) below black belt wear a white belt, with no distinctive markings. At 1st Dan (1st degree black belt) and beyond, one wears a black belt with hakama, the wide pleated pants of the samurai, to designate that you have reached that level in your training. Again, however, there is no distinctive marking for levels of black belt, either.

This is true except in some aikido lineages in which all women wear hakama, and those in which all students wear hakama, regardless of rank. There are other branches in aikido in which nobody wears a hakama, it’s just white and black belts.

So, yes. Rank is…ephemeral.

Rank can also be badly mismanaged, particularly at the black belt level. In the West, the holder of a black belt in the martial arts is regarded, wrongly, as an expert. But in truth a first degree black belt is only competent in the style’s technique. At that point, he or she is ready to begin more advanced learning.

Given that most people see the black belt as an expert, Western commercialization of many martial arts outside of aikido has resulted in the development of its own fast-food equivalent, with black belt rank being promised after only a year or two of training, or in promoting 12-year-olds to the black belt level — a guaranteed parent-pleaser that will help fill the kids classes, one of the most lucrative areas for many dojos.

Aikido has fairly well resisted that trend. The shodan, or first-degree black belt in aikido takes about 5–7 years of training, compared to 3–5 for most other martial arts, and the 1–2 years of training required by a McDojo. Aikido’s more extended time frame is not just due to resisting commercialization; the art itself is complex, with an endless array of variations on the basic throws and pins, and the aspiring black belt student needs to demonstrate a grasp of at least some of these. In addition, the first degree black belt test requires competency in bokken (wooden sword), jo (wooden staff), tanto (knife) and something not found in any other martial art that I know of: Defense against multiple attackers. Called randori, the test for any black belt level in aikido concludes with defending yourself against a minimum of four simultaneous attackers.

It’s not a test for the faint of heart (or short of breath). And where the average aikidoka reaches the black belt level in 5–7 years, I took about 15. Not all of them were that dedicated, as life threw a lot of boomerangs at me back in those days, but even if you eliminated my pauses, I did take much longer than the average bear.

My current Sensei has seen me pass through almost all the ranks, and she was the sensei who coached and cajoled me into taking my first black belt test a decade ago.

I balked like a stubborn mule the whole way, though. For the most part, I was simply afraid of facing my own incompetence, or looking at it another way, accepting my own competence. Dogged as I may have been in my training over the years, I have trained with many people with far greater natural talent and greater skill than I will ever have. It was hard to see myself on the same playing field as them. It has never been unusual for me to leave a class thinking to myself, “Goddamn, do I suck at this,” or something similar. The reason I’ve always kept coming back has not been to get good at doing aikido, but because I’ve always enjoyed the movement, the expression of physical conflict in graceful motion. And, over time, I didn’t necessarily get better at doing aikido, but I got much better at doing me because of aikido.

Not to say that I lack pride in my accomplishment. On the wall next to the desk in my office, are hanging five framed certificates, one for each level below black belt. In my main exam room, where every patient has their first visit with me, I have what I call my “brag wall,” with all of my diplomas, awards, and certificates relating to my profession as a chiropractor. On the opposite wall, hanging all by myself where nobody can miss it, is a large certificate, written in Japanese and framed in black. It is the certificate for my first degree black belt. On the one hand, it has nothing to do with my skills as a doctor, a physician, a healer; on the other hand, it has everything to do with those skills.

For Sensei to promote me to the next grade, nidan, was not just unexpected; it was like walking down the street, minding your own business, and suddenly being whacked upside the head by a bokken falling out of the sky. I guess, from her perspective, I can certainly understand her being comfortable promoting me without a test. After all, she has been my teacher since my days as a 4th kyu student. She knows my aikido probably better than I do. And I am truly grateful for not having to prep for another test.

The truth of the matter is, testing matters less and less through the increasing black belt levels. At that point the changes are more internal, more subtle. So I wondered what it was that Sensei was seeing in me, now, that would lead her to promote me. After all, I had only just finished my first year back in training after a near decade-long absence.

I thought about the changes I had gone through in the past year. First my physical struggles just to get through a class without dissolving into a little puddle of sweat and failure halfway through. And then my mental struggles, as my brain stuttered and shook like a Briggs & Stratton lawn mower engine trying to fire up on last year’s gas. I had to regain all that I had learned before, and put it into operation into this older, creakier and more dense body.

And I remembered when I felt that odd change occurring, those weeks when all of a sudden, everything started to move more smoothly. My focus changed, from the attack to the attacker, from their hands and feet to their face and eyes and even beyond. Recalling the advice that Takuan Soho, the Zen monk, had for his swordsman friend, the scion of the most famous sword school in feudal Japan: Let your mind rest on nothing, lest it be captured by your opponent. I was open, fully aware, and — and, well, feeling competent, for perhaps the first time during my life in the dojo.

It was about then that Sensei had me substitute-teach a few classes, and another awareness began springing into being. An understanding of things that I only got as a teacher, as I broke the techniques into components so I could reassemble them to teach in class. As I did that, my understanding of the techniques deepened in an unexpected way, and I could see all of the variations spinning off from the basic form of each. Now, when attacked, I am suddenly presented with a wealth of choices, an endless array of responses. I see them. They’re there, waiting for me.

When I first came to aikido, my only response to any conflict was a loud and aggressive “NO!” But as my skills grew, that simple angry word grew to a more complex response, something like “Left, right, or down.” Now, my vocabulary of conflict is a sentence that speaks not only of my response, but of my attacker’s aims. And, best of all, I have the response of no response: The strike that neither hits me nor slows me, as I walk past it, letting go of it as soon as it occurs.

Perhaps those are the changes that Sensei saw that impelled her to promote me. I’ll never know. It’s not something I would ask her.

Last week, we had our new year’s class, an extended class in which each of the black belts takes a turn teaching part of it, with Sensei herself taking the beginning and end. It was fun being both teacher and student at once. After class, we had a pot luck supper, at which Sensei announced my promotion, which had been approved by the higher-ups in New York and Tokyo, and the promotion of several others in our dojo, as well as some news of her own. It was one of those too-rare chances to enjoy all the other people who make my aikido experience as joyful as it is, without the strikes or the throws, just good food and camaraderie.

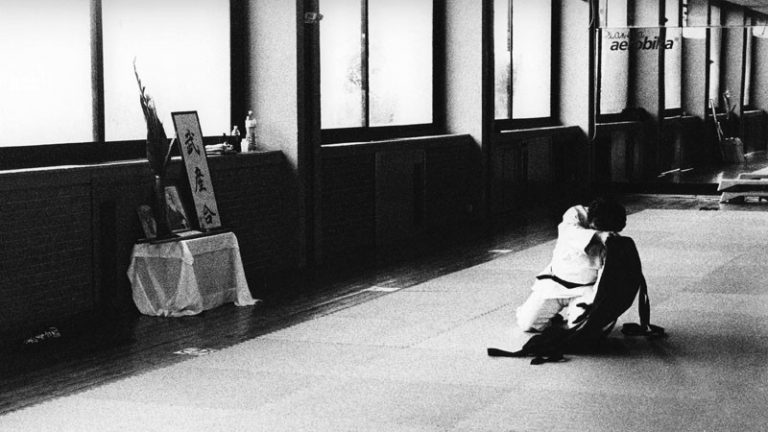

Later, I left the dojo, walking out into bitter cold, shocking even by crusty New England standards. But I barely felt it, nor the snow crunching under my feet as I walked to the car. It was 17 months ago that I had come back to this place, walking through those doors and bowing to the kamiza, not knowing if I could even still do aikido, not knowing if the broken man was mended. What I did know was that if he wasn’t mended by then, he never would be. I came looking for a place to be, a path to follow, knowledge that would help me mold these final decades of my life into the shape I wanted.

I exhaled, seeing my breath expand to fog and feeling it freeze on my beard. I looked back at the dojo, light shining from the windows, the kamiza, with its flowers and picture of the founder of aikido visible at the front.

I had found what I was looking for. And more.